Early European accounts provide insights into Aboriginal Australian social organization, revealing complex systems of land tenure, leadership, and group structure. A crucial starting point is the definition of “tribe.” As Lorimer Fison and A.W. Howitt cautioned, this term is deeply misleading. It could describe an entire distinct community, like the Larakia, or a smaller division within one. Early chroniclers, trying to understand these societies, left us a mosaic of observations about how people lived on this land.

Why Were Groups So Small?

Observers like Richard Sadleir and Roderick J. Flanagan pointed to a fundamental reality: the scarcity of reliable food in an uncultivated landscape. Flanagan theorized that the original inhabitants quickly divided into numerous small, mobile groups shortly after arriving, finding large numbers unsustainable for foraging. Sadleir observed that despite a favourable climate, the “want of food” kept populations low relative to the landmass.

Estimates of group size varied, but a pattern emerged: settled tribes were typically small. John Morgan, recounting William Buckley’s experience, described tribes of 20 to 60 families. Sadleir stated tribes rarely exceeded 50-60 people, splitting when they grew larger. While some reports mentioned tribes of up to 1,000, most chroniclers doubted this was typical for a settled community, suggesting a core group of around 200 adult men (about 1,000 people total) was more plausible.

However, George Taplin’s account of the Narrinyeri confederacy showed how several smaller tribes can come together to form larger ones in temporary alliances – like the 500 warriors meeting 800 opponents in 1849 – proving that those reports about a tribe getting up to 1,000 people were probably a combination of several tribes who came together for cooperation for specific purposes, especially warfare. Alongside the environmental constraints, practices like prolonged breastfeeding and infanticide were observed as factors that influenced population size.

The Bond with Tribal Territory

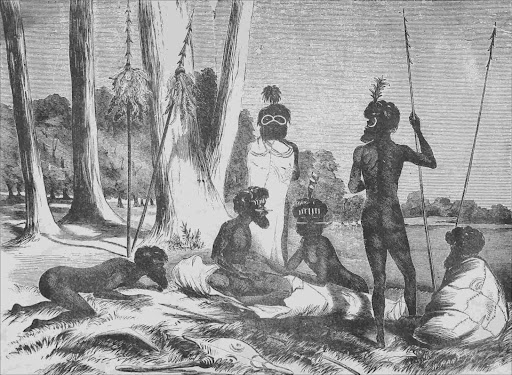

This brings us to the cornerstone of Aboriginal life: the non-negotiable connection to specific territory. Gideon Lang, Richard Sadleir, George Grey, and Rev. Dr. Lang all emphasized this with striking clarity. Each tribe occupied its own estate, “as distinctly defined as any estate in England” (Lang), with boundaries known intimately. Trespass by strangers was a capital offence, enforced without hesitation. Lang described how even individual trees could be owned property, recounting a poignant moment where his starving Aboriginal guide refused honey from a marked tree, stating it belonged to “another one blackfellow.”

Family groups within the tribe also held specific hunting grounds, passed down through generations. This deep territoriality, noted Sadleir, confined tribes to relatively small areas (often under 40 square miles), which itself contributed to periodic food scarcity. However, this exclusivity wasn’t absolute. Native laws allowed controlled access to vital, localized resources – like specific foods or materials – or for carefully arranged inter-tribal gatherings, negotiated with the formality of treaties between European principalities.

Leadership and Social Dynamics

There are different views about who held leadership roles within an aboriginal tribe. Sadleir noted that chiefs were often the oldest men. Morgan, however, observed a different model: tribes acknowledged no single supreme chief. Instead, the man proven most skilled, useful, and vital to the community’s well-being earned the greatest esteem and privileges, including potentially more wives. This polygamy, where older men might have three or four wives while younger men remained bachelors, was widely noted. Morgan also highlighted that conflicts frequently erupted over wives – involving theft, lending, or temporary exchange.

Conclusion

These early accounts, though filtered through a colonial lens, reveal glimpses of a sophisticated, pre-colonial Australia. They reveal societies adapted to their environment, governed by complex laws of land tenure, resource management, and social organization. Tribes, families, and individuals connected to the very soil they walked, a connection as vital as the air they breathed, long before European maps were drawn.